As a young woman and her family prepared for her wedding, they traditionally produced a dowry, which consisted of objects that would be useful to the woman in her new married life. They made utilitarian items such as bedcovers, wall hangings, tablecloths, mattresses and clothing, as well as textiles specific to the wedding ceremony—often incorporating kurak (patchwork).

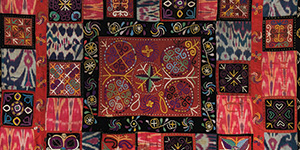

One significant dowry article of the Kyrgyz, Kazakhs, Tajiks and Uzbeks was the wedding curtain, usually made by the mother of the bride. It hung first in the home of the bride and then transferred to the home of her husband, where it created an area of privacy for the young couple. Customs varied but it was here that the newlyweds would spend their first nights. Tajiks frequently made the wedding curtain of kurak long before the wedding, sometimes even before the girl received a marriage proposal. The Kyrgyz of Djirgital, Tajikistan, prepared it only two weeks before the wedding and called for hashar, a communal coming together for work and socializing, much like the quilting bees of nineteenth-century North America. The family preserved it for future weddings, as well. Inhabitants of the Alai Valley of Kyrgyzstan used it to block evil spirits from entering the room.

In both nomadic and sedentary regions, the bride’s dowry also included a number of important kurak articles. Long rectangular mattresses (korpecho, korpa kurak, juurkan) stuffed with cotton for sitting and sleeping, were made of patchwork and quilted. Pillows, included in the bedding set, were flat and rectangular and consisted of a patchwork strip twelve to twenty inches long and six to eight inches wide, sewn to a plain piece of cotton. In order to prevent evil spirits from entering, the patchwork was folded in half so that the decorative edge of the pillow would always be visible. In the nomadic tent, this richly patterned and colored bedding pile, when not in use, was stacked on the floor, or piled aesthetically on a decorative metal or wooden trunk.